In a small English major corner of my being, I have always wanted to understand the War of the Roses which theoretically is covered in the Henry VI plays. Except that Shakespeare was a writer of historical fiction. Historians who are determined to get their facts correct prove, in doing so, why Shakespeare chose to fabricate and condense. No one would watch a play based on a chronology of history. Whatever else I have done after getting through the Henrys, I believe I have now got straight the chronology of all of Shakespeare’s history plays.

The Henry VI plays (there are actually only three) haven’t that much to do with Henry VI who would have made a better scholar or clergyman than a king. He’s like a piece of tofu. He doesn’t have much personality himself but he soaks up and disperses the flavors of a bunch of cut-throat, brave, bitter, enraged, funny, thoughtful, determined, and wily characters in the three plays that bear his name.

Part One:

The first play has a fabricated scene that suggests the War of the Roses began as a quibble among law students. They are making too much noise in Temple Hall so they go into the garden where they choose sides by picking white or red roses off the bushes. I made a list: White/York: Richard, Salisbury, Warwick. Red/Lancaster: everyone else. That wasn’t too hard. My college notes suggest I had the chance to do this 35 years ago, but apparently I didn’t.

The other attraction of Part One is Joan de Pucelle AKA Joan of Arc. She is portrayed, from the English perspective, as a witch, a whore, a liar. She is more interesting than the saintly Talbot on the English side who can do no wrong and who is quite boring until his son dies in his arms on the battlefield and he says, “and there died my Icarus, my blossom, in his pride.” That made me cry.

Part Two:

I loved Henry VI Part Two. I read it in one day like I would a fast-paced mystery that I couldn’t put down. It begins with the marriage-by-proxy of Henry to Margaret of Anjou. The insufferable Duke of Suffolk marries her in France and brings her to England to transfer the title to King Henry. She comes not only without a dowry but part of the deal is that England give back to France two of the provinces they had won during the reign of Henry V. No one is happy about this and everyone hates Margaret except for Suffolk and possibly Henry VI. It’s hard to know with him because he is so nervous and fussy and holy he might not recognize in himself anything so forthright as hate.

There follows a lot of deaths and banishments. Eleanor, the Duchess of Gloucester and wife of the king’s uncle and long-time guardian, is set-up to be caught in a séance wherein traitorous ideas are floated and she is sentenced to a penance of walking barefoot through the streets for three days with only a white sheet to cover her. The stage directions say “with verses pinned on her back.” I am guessing the verses outlined the charges against her and did not say things like “Kick me” or “I’m with stupid.” Then she is sent off to the Isle of Man for the rest of her life. I will remember Eleanor the next time I think I am having a bad day.

The next person to go is the Duke of Gloucester himself. He was arguably the only decent fellow at the court, always excepting the saintly King. The king faints at the news of the Duke’s death. When he comes to, he is distraught, thus giving Queen Margaret a chance to play the martyr:

Erect his statue and worship it,

And make my image but an alehouse sign.

Although almost everyone has reason to want Gloucester dead, Suffolk is implicated in the actual death thus allowing everyone else the chance to keep their dirty little motivations quiet a bit longer. He is given three days to get out of the country before he will be executed. On his way across the channel he is killed by pirates and his head delivered to Margaret who sobs over it. She always demands sympathy for herself that she does not extend to anyone else.

So it’s safe to say that things in England have escalated beyond a quibble among law students. The Elizabethans were even more obsessed with Order and Hierarchy than today’s Southern Baptists. Their worldview, the great chain of beings, was a hierarchy from God on down to the worm that turns. If someone gets out of line, it corrupts everyone and everything beneath. Fighting over the hierarchy of succession is the real cause of the War of the Roses. That pirates would kill a Duke is unthinkable and suggests that something is seriously wrong with The Order.

Then all hell breaks loose with a rebellion of what the aristocrats refer to as “the commons” and organized by one Jack Cade. The rabble races from southern England to London and drives the King and Queen to parts north. Their main complaints are the loss of provinces in France, their hatred of Queen Margaret, and their oppression by the learned classes.

Here is some reporting from the streets during the rebellion:

*We are in order when we are most out of order.

*I will make it felony to drink small beer.

*The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.

*Away with him, away with him! He speaks Latin!

*Thou hast men about thee that usually talk of a noun and a verb and such abominable words as no Christian can endure to hear.

(The following made me burst out laughing. The gang is playing with the severed heads of two courtiers:)

*Let them kiss one another, for they loved well when they were alive. Now part them again, lest they consult about giving up of some more towns in France.

Part Three:

In Part Three is the sobering scene of a world truly out of order. The stage directions say “Enter a Son that hath killed his father” and “Enter, at another door, a Father that hath killed his son.” Their speeches are heartbreaking. I have scribbled in the margin a note from a college lecture: “This is what it means to have a civil war.” Shakespeare’s timing is perfect. He presents us with these tragic figures when we are wiping away tears of laughter after the farcical Jack Cade’s rebellion.

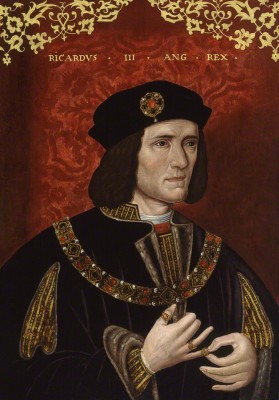

Underneath all the action, coolly biding his time is Richard, (York) who has a legitimate claim to the throne that has been occupied for six plays by the Henrys (Lancaster). He isn’t sorry to see Gloucester go. He has secretly incited the Jack Cade rebellion. He endures petty slights at court with great self-control. But he has laid the groundwork for an end he doesn’t live to experience.

The big event of Part Three for me was the recognition of a speech by the vicious and venomous Queen Margaret. One of my voice students (the Seattle area actor, Jenni Taggart) learned it for an audition and I got to watch it develop over the course of weeks while we worked on her vocal registers. Margaret torments the wounded Richard with a handkerchief drenched with the blood of his murdered youngest child–sweet Rutland—giving him the chance to call her a she-wolf and question the humanity of someone who would gloat over the death of a young boy. Let’s pause a minute and wonder if Margaret might have been slightly less horrible is she hadn’t been used as a bargaining chip and married by proxy, for God’s sake, to someone Match.com would never have put her with, then dragged across the channel to a country of sixty religions and only one sauce. Hmmm. . .nah.

Now pacing in the wings is the youngest son, Richard III, the greatest villain of them all and one of my favorite characters. But before I get to him, here are more memorable lines from Henry VI:

Part One:

*Glory is like a circle in the water

Which never ceaseth to enlarge itself,

Till by broad spreading it disperse to nought. (I, ii)

*Unbidden guests are often welcomest when they are gone (II, ii)

*I’ll note you in my book of memory (II, iv)

*She’s beautiful and therefore to be wooed;

She is a woman, therefore to be won. (V, iii)

Part Two:

*Could I come near your beauty with my nails,

I’d set my ten commandments in your face. (I, iii)

*Smooth runs the water where the brook is deep. (III, i)

*What stronger breastplate than a heart untainted. (III, iii)

*So bad a death argues a monstrous life. (III, iii)

*The gaudy, blabbing and remorseful day

Is crept into the bosom of the sea. (III, iii)

*Small things make base men proud. (IV, i)

Part Three:

*The smallest worm will turn being trodden on. (II, ii)

*Things ill got had ever bad success. (II, ii)

*Ill blows the wind that profits nobody. (II, v)

*Both of you are birds of a selfsame feather. (III, iii)

*Suspicion always haunts the guilty mind. (V, vi)

*He’s sudden if a thing comes into his head. (V, v)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed