Richard III

I have a Shakespearean Insults coffee mug. As I read Richard III, I noticed that a fair number of the slurs from the coffee mug were ones directed at Richard:

*Lump of foul deformity (I, ii)

*Diffused infection of a man (I, ii)

*Thou canst make excuse current but to hang thyself (I, ii)

And these were delivered by the woman he was shortly to marry! He interrupts the funeral procession of Henry VI to propose to Henry’s daughter-in-law whose husband Richard has also killed. And sure enough by the time the Lady Anne has spit out enough insults, a creepy sort of sexual chemistry has developed.

Then our old friend from Henry VI, Queen Margaret, rears her vicious head says:

*Thou elvish-marked abortive rooting hog! (I, iii)

*This poisonous bunch-backed toad (I, iii)

So he wasn’t the sweetest guy. Richard himself says:

*Since I cannot prove a lover

To entertain these fair well-spoken days

I am determined to prove a villain. (I, i)

Richard is introduced in Henry VI Part Three. King Henry holds forth at the end of the play:

*The owl shrieked at thy birth, an evil sign;

The night crow cried, aboding luckless time;

Dogs howled and hideous tempest shook down trees. . .

Thy mother felt more than a mother’s pain,

And yet brought forth less than a mother’s hope,

To wit, an indigested and deformed lump. . .

Teeth hadst thou in thy head when thou wast born

To signify thou cam’st to bite the world. . .

Richard puts a stop to this litany by killing Henry. Then he carries on with:

*And this word ‘love,’ which grey beards call divine,

Be resident in men like one another,

And not in me. I am myself alone. (Henry VI Part Three, V, iv)

Tho I wouldn’t want to live next door to either of them, I feel drawn to Richard III, kind of like I feel drawn to Stieg Larson’s Lisbeth Salander. My mother rarely missed a chance to let me know that I was “less than a mother’s hope.” But it is the line “I am myself alone” that touched me, especially during the earlier part of my life when I was depressed and lonely. I sympathize with Richard even though my deformities were imagined and my murders were symbolic.

After his eldest brother, King Edward IV, dies, Richard manages to snatch the crown even though there are a dozen people ahead of him. A weasel-like Eddie Haskell character, he goes about the deadly business of making his position secure. He has the middle brother, the Duke of Clarence, killed, and the story gets about that Clarence was “drowned in a butt of malmsey.” Richard has it put about that some of his rivals were illegitimate. He does away with a number of lords who arouse his suspicions and even poisons his own wife. His sadistic and sneaky crimes are compounded until he has his two small nephews, Edward’s sons, murdered. After this, he starts to decompensate. His paranoia becomes profound and his erratic behavior loses him so much support that even his horse deserts him. He dies in battle screaming,

*A horse! a horse! my kingdom for a horse!

So here’s the thing: as irritating as it is to encounter Isaac Asimov’s frustration over every single note of Shakespeare’s improvisations with historical fact, I concur and cheer him on when he says that nothing in Shakespeare’s characterization of Richard II is true. The historical Richard was quite a lovely fellow.

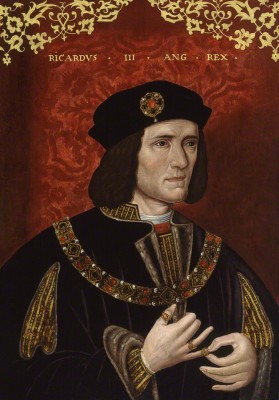

Josephine Tey, (aka Elizabeth Mackintosh and Gordon Daviot) classic writer of murder mysteries, has written a great little book called The Daughter of Time. Her detective, Alan Grant, is laid up in hospital recuperating from having fallen through a trap door whilst in pursuit of a criminal. To while away the time he researches the history of Richard III. His actress friend brings him a copy of the portrait of Richard from the National Gallery in London. She says his face is “full of the most dreadful pain.” Grant’s nurse says the man in the portrait has a liver disorder. His surgeon says he had polio-myelitis as a child. His sergeant pegs Richard as a judge. No one thinks it’s the face of a murderer.

As Grant finds out, the historical account that everyone cites for Richard was written by a shill of Henry VII who Henry then made Archbishop of Canterbury. Sir Thomas More took up the slander without questioning its validity and his account made it into both legends and history books which is where Shakespeare found it.

But Grant is a policemen. He looks at what people actually do, where they are, what are their alibis and what eye-witnesses say. His research assistant find records, letters and histories written while Richard was alive. Turns out he was wise, generous, courageous, able and popular. There was no outrage about any nephews in the tower being murdered while Richard was alive. The outrage came two year’s later when Henry VII’s lackey put it about that Richard had murdered the boys. What seems more than likely is that Henry VII was the one who had them murdered. In fact Henry VII seems to resemble the Richard in Shakespeare’s play in everything but the hunched-back and the shortened leg. It wasn’t politic to say any of this until the last of the Tudors was gone. The record was corrected when James I succeeded Elizabeth I.

The evidence in the case has been known and conceded for hundreds of years but the insistence persists in some dark corners that Richard III was a villain. This I think we can lay this at the feet of Shakespeare who created a memorable, indelible character that we love to hate and hate to love. The odd thing is that though I love the idea of Richard III being a good guy, I still am charmed and mesmerized by Shakespeare’s villain. I am glad they are both there.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

Leave a Reply